| The

Choirboy Stone

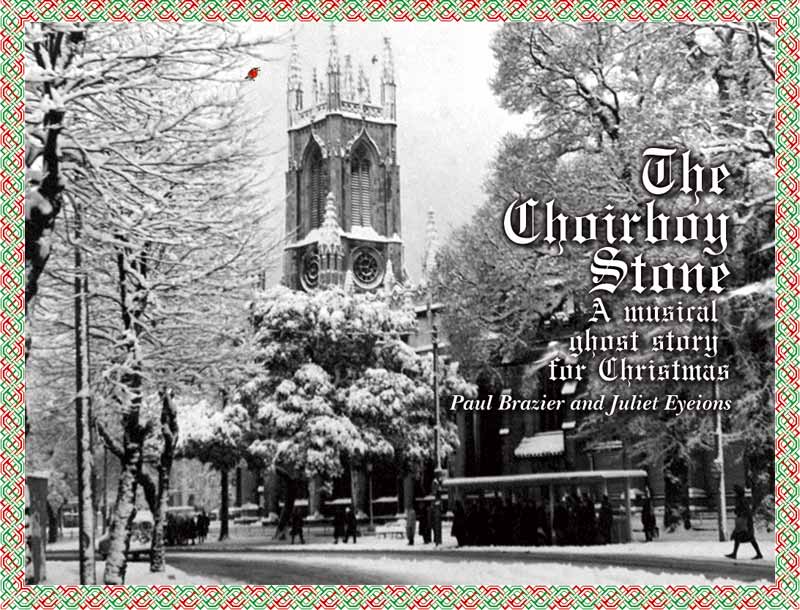

a musical ghost story for Christmas Paul Brazier and Juliet Eyeions The wind howled and blew snow in the face of the boy. He wrapped himself tighter in his ragged blanket and, too cold even to shiver, stumbled up the steps of the church. Its windows glowed with candlelight and singing could be faintly heard through the thick oak doors. If he could no longer sing, at least he could listen. He tried to turn the heavy handle, but his frozen hands slipped off it. He banged on the doors but to no avail – the sound was lost between the storm and the singing. He coughed quietly into his hand and knew the bright redness that was there, even in the gloom. He curled up out of the wind on the great stone bench by the door and listened as the choir, his friends, sang the midnight mass. A

robin singing in a tree outside was He liked to be on-site early to investigate the foibles of acoustic spaces he had to work with. This church was a dream – very different from the cold, echoey ambience he usually found in churches, its presence was almost as if someone had just stopped singing and the notes were still ringing. He hoped it would sound as warm for the next concert – tearing it down and reassembling it elsewhere was bound to change its acoustics. But the new sports stadium, gyratory and rail terminal planned for the town centre where the church and trees now stood meant they simply had to go. The trees, in the last stages of Dutch Elm Disease, were unsalvageable but the church had been the subject of a concerted preservation campaign – to the English, only pubs and churches seemed to be sacrosanct, and the local preservation committee had managed to fight the development plans to a standstill, even though the building was in very poor repair. Finally, an enlightened but anonymous donor had broken the deadlock with a scheme that encouraged people in the local community to adopt a stone of the church and pay to move it. The donor would match the funds thus raised and, when enough stones were adopted, this would pay for the entire church to be dismantled and rebuilt in a more convenient locale. Tonight’s concert of early and contemporary choral music was intended both to finish the fund-raising and symbolically to mark the lifetime of the church and its rebirth in the 21st century. It was being broadcast by the BBC and, once the move was complete, a similar concert would be broadcast from its new prime location on the top of the downs, close by the race course, the hospital and the cemeteries, overlooking the city that was its birthplace. * * * * * * At the station, there were no cabs to be had. The well-known soprano had asked specifically not to be met, as she liked to get a feel for a new town on her own, so she left her overnight bag in a luggage locker and set off down the hill to find the church. It was treacherous underfoot, with the recent snow camouflaging ice and slush, but she reached the church without mishap and the great doors stood invitingly open. She had been rehearsing her part in her head as she walked and had just arrived at one of the glorious soaring high Cs. As she stepped up to the porch, she felt a tickle in her throat, coughed, her foot slipped behind her and she stumbled, banging knees and shins on the steps. Clambering up them, she sank onto a great stone bench, grateful for the opportunity to brush the snow and ice from her coat and throbbing knees and gather her wits. Leaning back, she put her hand out to steady herself against the wall. A small movement caught her eye. A mouse? No, a robin hopping into the porch with her. At that moment, she heard the line of music she had been rehearsing rise within the church, but sung by a perfect boy soprano. She stood up abruptly and, through the doorway, saw a lone choirboy standing singing before the rood screen and the chancel. A whirr of wings behind her made her look round, startled, but when she looked back both boy and robin were gone. She felt letters in the rough stone under her fingers and looked more closely. In Memoriam, it read, then a name that was obliterated by wear, then a date, Christmas Eve hundreds of years ago and the legend – He will always Sing in Our Hearts. “Are you all right?” She looked round and saw an absurd sight – a young man in a clerical collar, a huge khaki army great coat and a russian-style hat was standing at the bottom of the steps holding a shovel. “I saw you stumble just now… but you’re –” “I’m tonight’s soloist, yes,” she admitted. “Tell me, who is that singing in the church?” “There’s no one in there, as far as I know. Apart from the sound engineer, that is. Perhaps he was playing a recording to get his levels right. But your knee!” His shovel clattered to the ground as he bounded up the steps. “You’re bleeding. Look, come to the vestry and we’ll get you cleaned up.” * * * * * * * When she arrived for the rehearsal that afternoon, she found a line of boys in red blazers filing into the church through the porch and was bemused to see each boy run his fingers across the In Memoriam stone she had discovered that morning. They proved to be the choir from the school affiliated with the church, and she was glad to discover they sang superbly. The church, too, lived up to its reputation as the perfect setting for Allegri’s Miserere, especially as it was approximately the same age and so a candidate for where the piece had first been performed in England. As the final resonances faded away, there were smiles all round and the choir master came over to shake her hand. Everyone knew it would be a great concert tonight. Stepping down from the podium, she met the sound engineer strolling down the aisle from his booth. “Are you happy with the sound?” he asked. “It’s glorious” she replied. “Why? Did you have any problems?” “I really can’t describe it.” he said. “Not problems, no, because the sound is so wonderful, but… you know every good acoustic space has a sweet spot, a place where all the echoes cancel one another out so you can put a microphone there and get a reference recording?” “I didn’t, but if you say so…” “Well, finding it is more art than science, but that microphone there –” he pointed high above their heads – “is as well-placed as I could make it, and this morning I was getting perfect sound from it. But during the rehearsal there, it seemed to me I was not hearing you on your own. It wasn’t an echo, though… more like the sound was doubled, as if someone were duetting with you and you were helping each other to the high notes.” “It felt that way too,” she said quietly. Her throat was beginning to feel sore. She was sure she was developing a cold, but equally certain she would be able to perform this evening, before it took her voice. “I thought it might be something to do with the bird,” he said, pointing. The red breast was clearly visible on top of the microphone. “But the only thing I ever hear is the occasional whirring of its wings. I don’t know of any way it could affect the recording.” “In that case, we won’t worry about it,” she responded. “I’m happy to have any help I can get.” * * * * * * * That evening, she took her place on stage in front of an audience of the great and the good who were probably there as much to be seen as to hear the concert. She chastised herself for a cynic. It was probably the rising tide of fever. But she could still sing. The choirmaster raised his hands, paused, and with his gesture the choir’s voices took flight behind her. They feathered the choir stalls and brought back wood, brushed the walls and brought back stone and resonance. She was fi lled with the heady joy of great music as the great wings of song brought the rapt attention of the audience and lifted her into her moment to fly with them. She breathed in, opened her mouth and felt the tickle all singers dread, the feather in the throat, the drying, the cough coming but, instead of a cough, the music filled her and seemed to help to draw her voice forth until the thrilling high C transfixed everyone as she and the church and the music became one. She came to herself and heard the final notes ringing away into the vaulting roofs. Her head swam, her throat was closed and her face glowed – then the audience was on its feet, clapping and cheering – but all she could see was the bundle of red feathers perched on the microphone. ******* The following morning, before leaving, she returned to the church and found the vicar and choir outside the church in full regalia. “How’s your knee?” he asked. “Fine, fine… what’s going on?” she asked huskily. “It’s the deconsecration ceremony. They can’t build here while this is consecrated ground. We’re waiting for the bishop but I think he must be stuck in traffic,” he said, indicating the gridlock around them. “Did you come to see the service?” “I’m sorry, if I had known about it I would have loved to, but I have to catch a train, I’m afraid. Although, if my voice fails completely, I might not be able to perform tonight. No, I came to ask if it was too late for me to adopt a stone?” “Of course not. Many stones are double-subscribed anyway. We’re not exactly going to turn money away. Any particular one?” he asked lightly. “Yes, actually.” Something in her tone took the smile from his face. “The little memorial stone in the porch by the bench.” “You mean the choirboy stone?” “If it’s the one that says he will always sing in our hearts, yes. Why do you call it that?” “The tale in the church tourist pamphlet says his name was Christopher Hood and he was a chorister in one of the first choirs when the church was new. He loved singing more than anything but developed consumption and couldn’t sing any more. Finally, he came to the church on a freezing snowy night to hear the midnight mass but, unfortunately, he didn’t have the strength to open the door and they found him frozen to death on that big stone bench in the porch at the end of the service. He was only twelve years old. The locals loved his singing so much that they all chipped in to put up that memorial stone. In fact, we used the story to get adopt-a-stone going but I don’t believe a word of it myself. It’s a lot of silly sentimental Victorian tosh, if you ask me.” “What are the choirboys doing there now?” “They have a tradition – a pagan superstition, more like, which good Christian boys should ignore, I say, but they pay me no mind. little heathens – that the spirit of the choirboy can be invoked to bring them luck in singing exams and help with difficult passages when they are performing. All they have to do is trace out his name. Of course, centuries of boys’ fingers have worn the name away completely so now they just run their fingers across where his name was. But they still claim it works and that’s what they’re doing now.” Birdsong in the tree above their heads vied with the traffic as it grumbled and ground forward a few feet, and a limousine pulled up. A door opened and the bishop began to emerge. “I have to go,” she said. “Please make sure I am included in the adopt-a-stone scheme. I’ll see you in five years.” * * * * * * * Five years is not a long time in the career of a soprano but from this moment on, she was always in demand. Critics could not agree whether it was the overall quality of her voice or some individual element – the tone, the expressiveness, the richness, the power – that had improved, but all agreed that every concert she gave was more glorious and sublime than the last. Her fame grew even beyond the music community. She appeared on arts shows on television, then chat shows with famous hosts, and, finally, when one of her recordings was used as a theme for the Olympic Games, she became a household name. Such celebrities have engagements booked months and even years ahead, but through all this she ensured she kept the return date clear for the reopening of the church on the hill. Unfortunately, building works are not so certain and, when the reopening of the church was delayed by nearly four months, regretfully she had to give up the opportunity to sing in its opening concert in order to honour a contract in the far east. So the irony was doubly bitter when the concert for that night was cancelled at very short notice because the impresario, Brother Orchid Pooh Sin, turned out not to be a Buddhist monk but a con man who had absconded with the funds and not booked the venue. However, it did mean she could attend, and a taxi dropped her at the hill-top site in the early afternoon of a beautiful spring day during the final run-through of the next day’s concert, which would also be in the afternoon, as no public transport provision had yet been made to get to the church in the evening or on Sundays. Not wanting to disturb the performers, she entered by a side door she knew the sound engineer used and, after negotiating an extra interior glass door, was pleased to find him in his booth just inside. She was even more pleased to find he was the same engineer she had met five years ago. “Well?” she asked. “Is the sound as good?” “No,” he said glumly. “It’s cold as the grave.” She stepped out of the booth. The replacement soprano was doing a good job on the music but the sound was thin and cold and the accompanying choir sounded like a flock of timid sheep bleating along with her. Leaning back into the booth, she asked, “Why do you think that is?” “There have been a lot of changes,” he said. “They’ve used modern materials, double-glazing to keep it warmer, padded chairs instead of benches and there are new glass enclosures around all the doors to make the place more energy efficient…” “…but those aren’t really the things that are wrong, are they?” she interrupted. “It’s the spirit of the place that has gone!” She stepped back out of the side door and made her way round to the grand front porch. As she mounted the steps, the vicar appeared from the opposite direction, wearing wellington boots, corduroys and a plaid shirt and holding a spade. “Hello, again,” he said. “Come to look at your stone? Wonderful view from up here, eh?” He turned to look across the town to the sea gleaming under the spring sunshine beyond. The taxi had approached from the other side of the building, so she hadn’t noticed before, and the view took her breath away. What a glorious location for music. This could not be allowed to fail. She looked back to the vicar and saw he had been digging a new flower bed. A robin flew down from nearby bushes and pecked at the soil. “Have the choirboys been practising in the church?” she asked abruptly. “Well,” said the vicar, “the school had to make other arrangements while the church was being moved and in the meantime they have started admitting girls. Now, the governors don’t think it is appropriate for a mixed choir to travel all the way up here unaccompanied with the limited public transport so, no, the choir has carried on singing in the school.” “Get them up here tomorrow for the concert. We can make a late addition to the programme, myself and them performing the Miserere again, to echo the last performance here. And keep them coming, or both your church and its music will die.” She ran up the steps, ran her fingers firmly over the choirboy stone, threw open the doors and strode into the church as the last strains of the music died away. And behind her she was not surprised to hear the faint whirr of wings. * * * * * * * The following afternoon, after only the briefest run-through of the Miserere with the choir in their schoolroom that morning, she took her place on stage in front of an audience bubbling with anticipation. The choirmaster raised his hands, paused, and with his gesture their voices murmured into life behind her. Like a rising tide, they lapped over the wooden choir stalls, touching and rippling from the walls, filling the nave and chancel, the aisles and the apses, and washing over the audience until the flood of music came rushing back from the church, buoying her into her moment to join their song. Her voice became a fountain, springing from her effortlessly, filling the church to the brim and she forgot to breathe, to think, and simply floated, the sound cascading around her, as she and the church and the music became one again. When she came to herself, she heard the final notes of her solo ringing away into the vaulting roofs and then the people were on their feet, clapping their hands sore and cheering. She bowed and left the stage but was called back for further adulation which only ended when the lights were brought up for the interval. While many were speculating as to whether she had inadvertently overshadowed her stand-in for the second half of the show, she took two glasses of wine and slipped into the sound booth. “Well, how was that?” she asked the engineer, handing him a glass. “Thank you. Magnificent! The moment the children started singing, the old ambience started to creep back and when you joined in, it seemed to kick in with all its force. How did you do it?” “‘It’s more an art than a science.’ You have your trade secrets, I have mine.” “Fair comment. Well, now it’s back to it’s old state, I hope to hear many more concerts from here. Cheers!” He lifted his glass to her. * * * * * * * Much to everyone’s surprise and delight, the second part of the concert was as good as the first, the stand-in soprano plainly rising effortlessly to the challenge. As the applause subsided, the vicar stepped onto the stage wearing a surprisingly sober black shirt and trousers with his clerical collar, and delivered a speech of thanks to everyone for making the reinauguration of his church such a wonderful occasion. He then announced, to rapturous applause, that the governors of the choir school had got together in the interval and invited the world-famous soprano to take over the role of musical director and choirmaster from its retiring incumbent and that she had accepted. She stepped back onto the stage to cries of “speech, speech!” and, once the hubbub died down, said, “Thank you all so much. When I first came to this town, I saw it as a stepping stone in my ambition to travel the world with my art. Well, something happened at that concert that changed me profoundly. I can’t say if it was me or the church or the combination; all I know is that my success over the past five years began here and it is both my duty and my pleasure to take up the challenge of giving something back. “I can’t do this on my own, of course, and I would like to thank the vicar for all his help so far. I look forward to a long and fruitful relationship with him in future as well. I would also like to thank the outgoing choirmaster and musical director and, of course, the governors, who have also made my next announcement possible. “The most important person we need to thank can’t be here in person, although sometimes I feel he is with us all the time. Five years ago, I didn’t know he had ever existed. Now, without his dedication to, and love for, music, I doubt we could have achieved all we have. You’re all familiar with his story from the adopt-a-stone campaign, and I am thrilled to announce that this date each year will be marked by The Christopher Hood Memorial Festival of Choral Music!”

The roar of applause that greeted this could be heard clearly outside The Church On The Hill, as it was becoming known. A passing child, drawn to the new building by the beautiful sounds she had heard coming from within, sat on the great stone bench in the porch, her legs swinging. Idly, she fingered the stone with the funny writing and wondered what In Memoriam meant. Lights within made the windows glow as the twilight crept over the sea behind the church. And, in a nearby tree, a robin sang the sun to its rest. * * f i n * * The

Choirboy Stone is copyright © 2005

Back to Xmas story index | home | Merry Christmas |