In his own words

This is a selection of extracts from Hodgson's writings, dealing variously with his own work and life.

|

||

On life at seaHodgson was the great horror writer of the sea. Despite the focus of this site it is arguable that his best short work is found in such stories as "The Voice In The Night". Hodgson ran away from his mother and clergyman father at an early age, eventually getting apprenticed at sea. He lasted as a seafarer for eight years; in 1899, he quit life as a sailor passionately hating it and accusing those around him of frequent brutality. ". . . being a little chap of very ordinary physique I had the misfortune to serve under a second mate of the worst possible type. He was brutal, and though I can truthfully say I never gave him just cause, he singled me out for ill treatment. He made my life so miserable that in the end I summoned up sufficient courage to retaliate and "went for him". It was for all the world like a fight between a mastiff and a terrier, for he was powerfull and knew how to punish. Of course, I took a merciless thrashing".

"I am not a sea because I object to bad treatment, poor food, poor wages, and worse prospects. I am not at sea because very early I discovered that it is a comfortless, weariful, and thankless life - a life compact of hardness and sordidness such as shore people can scarely conceive. I am not at sea because I dislike being a pawn with the sea for a board and the shipowners for players." One may guess how Hodgson's experiences as a fairly small, weak, young man at sea informed his vision of the Night Land, and particularly of the Giants. | ||

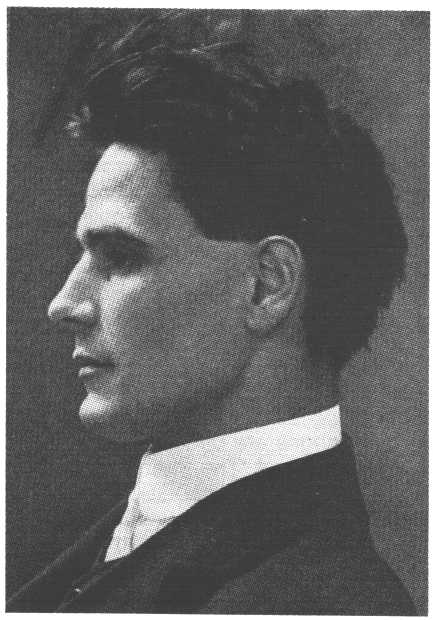

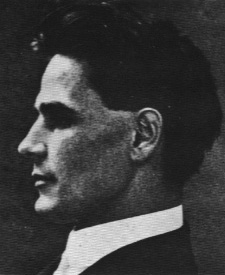

On "physical culture"Hodgson was a short man of "very ordinary" build who suffered greatly from bullying in his early years in the Merchant marine. He resolved to compensate for his lack of inches by exercise. This extract from a letter, written in 1905, to a fellow writer, one Coulson Kernahan, may make the outstanding physical strength of Hodgson's heroes a little more credible. "My dear Sir, let us shake hands on this further matter; for strength has been and is still -- in spite of indifferent health -- a thing of tremendous interest to me. "From your remark, I gather that the gods have given you a length of seventy two inches, while they have given this child something under sixty six. With such length I refused to be content, so make it up in breadth and muscularity. "Sometime, if you would really care to have one, I must send you a decent photograph of myself, showing developement. In the meanwhile I have snipped you out a couple of weeny ones from some old postcards of mine. They may interest you. "Of course, I'm nothing like as strong as I used to be before the flue bowled me over last year, and left my heart a wee bitte weak. Also, I think that writing has taken off a lot of muscle --- confound it! But I suppose one musn't be greedy. "Before I was ill, I could take two fifty-six pound weights in one hand, and put them at arm's length over my head, and, in fact, lift a good deal more than that with more convenient weights. Now, I very much doubt if I could lift more than eighty or ninety pounds over my head with one hand. Another thing, I could lift considerably more than a quarter of a ton off the ground, using my bare hands -- no straps around hand and wrist. And that takes a bit of doing. And now -- well, if I go easy I daresay I shall come back to my old form in time --- let but the editors smile on me a bit."

| ||

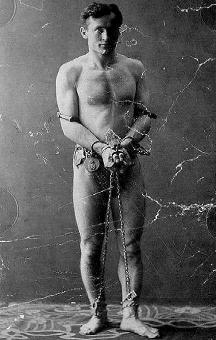

Hodgson Vs HoudiniHodgson ran a "School of Physical Culture" in Blackburn in 1902 and 1903. In 1902 he squared up to Houdini. The following notices appeared in the Northern Daily Telegraph (24 and 25 October 1902 respectively).

| ||

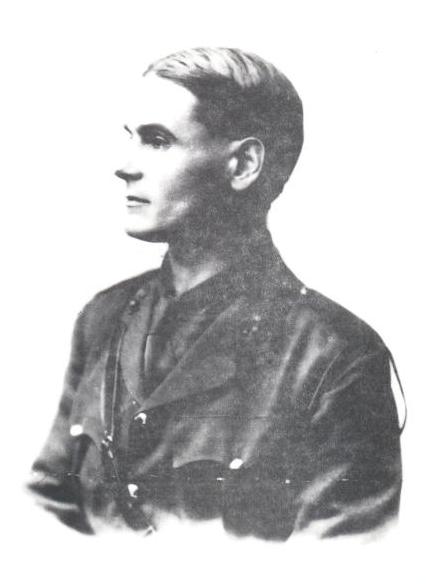

From the trenchesHodgson died in the trenches in 1918. This extract from one of his last letters, written early in 1918, is provided by Philip Ellis, and was part of an obituary in ((magazine???)) "What a scene of desolation, the heaved-up mud rimming ten thousand shell craters as far as the sight could reach, north and south and east and west. My God, what a desolation! And here and there, standing like mute, muddied rocks-somehow terrible in their significant grim bashed formlessness-an old concrete blockhouse, with the earth torn up around them in monstrous craters, and, in some cases, surged in great waves of earth against the sides of the blockhouses. The sun was pretty low as I came back, and far off across that Desolation, here and there they showed--just formless, squarish, cornerless masses erected by man against the Infernal Storm that sweeps for ever, night and day, day and night, across that most atrocious Plain of Destruction. My God! talk about a lost World--talk about the END of the World; talk about the "Night Land"--it is all here, not more than two hundred odd miles from where you sit infinitely remote. And the infinite, monstrous, dreadful pathos of the things one sees--the great shell-hole with over thirty crosses sticking up in it; some just up out of the water--and the dead below them, submerged. And near the centre there was one cross inscribed to "Adolphe Dehaut, tué Nov. 26th, 1917." And on the centre of the cross, lashed with a piece of cross-wire, was an empty bottle, upside down. ("Turn down an empty glass," I suppose.) Who, I wonder, was Adolphe Dehaut? If I live and come somehow out of this (and certainly, please God, I shall and hope to) what a book I shall write if my old "ability" with the pen has not forsaken me. Who, I wonder, was Adolphe Dehaut? Some day, if it please God, I'll see that at least one French soldier's name is not lost in the dreadful oblivion that, like the mud of this hideous world, falls on the dead, and they pass out, wrapped in their blanket."

| ||

WILLIAM HOPE HODGSON'S BLACKBURN HOMEThis account is from the pen of a UK fan, Steve Sneyd Back in 1988/9 , having read - I now forget where - not only that William Hope Hodgson had lived for some time in Blackburn, Lancashire, but, of particular interest, that his idea for the mysterious dwelling of `The House on the Borderland' may well have been influenced by his Blackburn home, I made attempts to find out where that home had been. The Borough of Blackburn Community & Leisure Services Department had "nothing on file for Hope Hodgson" and did "not have the book" - their Lyndsey MacDonald, indeed, suggested that I might have the wrong Blackburn, there being at least four others. But J B Darbyshire FLA, District Librarian of Lancashire County Council's District Central Library, and subsequently a Mr Sutton of the same library, proved to have the answers in terms of not one, but two, exact addresses, between them covering Hodgson's five years in Blackburn. I had good intentions to pay a pilgrimage as soon as possible. Events supervened, time did what time does, and years went by. Then I saw mention of a Fantasy Art 2001 AD exhibition at Blackburn Art Gallery, and was reminded of the Hodgson house matter. Amazingly, I outwitted my filing system, and found the data from the late `80s. On the very last day of the exhibition, it was off to Blackburn.

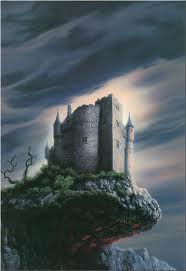

It seemed appropriate that the art display included a Jim Burns

illustration of "The House On The Borderland (Hodgson)",

presented as a striking medieval castle, After the exhibition, now to find those Hodgson addresses. I looked at the letter again: "Further to our telephone conversation regarding the Blackburn residence of William Hope Hodgson, I write to inform you that he was never a householder and, as he was only 20 when he opened his gymnasium, it is difficult to trace him from electoral registers. In 1903 he was lodging with Mrs. Elizabeth Sarah Hodgson, presumably a relative, at No. 2 Park Mount, Revidge Road. Assuming that he stayed with her for all his period of residence in the town, then his address would be 16 Henry Street, Blackburn, from 1899 to 1901 and 2 Park Mount from 1902 to 1904. Mrs Hodgson stayed on at the house which she owned and which was renumbered 307 Revidge Road in 1907. She had left the area by 1908." The helpful woman in the Tourist Information Office didn't enquire why I wanted to know where these addresses were - they clearly rang no bell for her. Henry Street, she explained, had long since been demolished in slum clearance. However, Revidge Road was still there, and she photocopied me a street map. It was, according to the map, a VERY long road, a bit north of the town centre. She suggested a bus that would take me to one end of the road but the day was pleasant, and the streetmap showed a large park running from Preston New Road, which began in the centre, right up to Revidge Road. Up proved to be the operative word.The Corporation Park, entered by an imposing arch in the style of a decorative city gate of the Roman Empire, "Erected 1854-5 in the Mayoralty of Thomas Dugdale" (another notice explained that the whole park was officially opened in 1857 by William Pilkington, Mayor) began fairly narrow, but fanned out to a considerable width. Its paths also proliferated - but all of them shared the characteristic of climbing, continuously and steeply, the only level area of the whole park being that occupied by two ornamental lakes. My selection of paths was random as I climbed. At last, having slanted up to the left above a pair of tennis courts, I reached the top of some steep steps to the right off a wider track, and found myself finally at the summit. In front of me a road, which had to be Revidge Road according to the map; and, across the road, houses. More precisely, immediately facing me was the end house of a short terrace of small two-story stone cottages, obviously old. I crossed the road to look at the numbers, to find out where on Revidge Road I had come out. And was left feeling very surprised and a little shivery. I had left the Park by the one path, out of many I might have picked along its considerable length of Northern edge, which came out immediately opposite number 307 itself, Hodgson's old home. The house's location is itself on what could be called a kind of borderland. It is on a ridge that in one direction, that from which I had come, overlooks the town, a view of buildings as far as can be seen. But in the other direction, because this is the end of the built-up area, the view is very different, out over a golf course and small grass-covered water tank, with beyond them nothing but empty moorland into the distance. To the house's east, there is the gap of an unmade road onto the golfcourse, before an extremely long Victorian terrace begins. To the west of the group of three old houses to which it belongs, there is a large public house or inn, on the far side of which a high wall holds back higher shrubgrown ground, well behind which must lie the microwave transmission tower that had dominated the skyline when looking upwards from the town centre; at this point Revidge Road drops away steeply down towards the continuation of Preston New Road. Like its two adjoining neighbours to the West, 303 and 305, 307 has a small garden to the front.The four front windows, two on each floor, are modern insertions. I went along the track east of the house, oddly named Red Rake, to get a view of the building's side and back. A projection gives it an overall L shape; on this side there is one large window above, and two very small ones on the ground floor. The back can be reasonably well seen over the high wall of a smallish back garden: at the junction of the L is a square "stair tower", and the garden area ends to the West with another projecting extension, this time of 305, although a lower slateroofed structure immediately behind 307 appears to be part of it, not its neighbour. Nowhere was there any blue plaque or other indication that a notable writer had once lived here. I then walked past the front of the other two cottages, to the Corporation Park pub building which ends the group. Much larger and taller than its neighbours, built in red brick, and looking late 18th or early l9th century, this has an exterior nearer the necessary size for the book's house than the little cottage, but otherwise it in no way matched the description. Rather than "curious and fantastic to the last degree", it was just a solid plain bit of copybook Georgian, with no sign of "Little curved towers and pinnacles, with outlines suggestive of leaping flames". Moreover, far from having a "body" in "the form of a circle", it was a straighforwardly rectangular structure. Ah well, time for a drink before I went. So I went in. Now THIS was more like it. HERE were the "empty rooms and corridors" of the Borderland house, the bar area already full of dusky gloom although it was only midafternoon. The only other customer watched the TV to learn of Blackburn Rovers' half-time score; his dog persistently attacked, caught, and chewed beermats. A landlord dark of suit, his head totally shaved, prowled gloomily. The other customer left. The landlord wandered away into some Private realm behind the public scene. And, for a few minutes, the place to myself, the chattering TV commentary mentally tuned out to gibberish, dwindled away to the calling of distant, horrid creatures, I was wholly convinced that this old, gloomy, high-ceilinged interior was indeed where an inspired Hodgson had found the setting for his masterpiece of cross-temporal terror. And those few minutes made the whole Blackburn "pilgrimage" worthwhile. | ||

Scraps / From HopeThis interesting tit-bit is taken from Jane Frank's compilation of rare Hodgsoniania, THE WANDERING SOUL. The following passage was inscribed by hand on the endpaper of a copy of THE NIGHT LAND which Hodgson gave to a girl he called "Scraps" in 1912.

"Scraps" was one Wilhelmina Bird, the very young daughter of a friend. Hodgson apparently struck up a friendship with the Bird family some time before 1905, one close enough for him to stay with them for a month at the start of that year. He sent their young daughter several first editions of his works between 1907 and 1916. She was eighteen years his junior and to what degree she was an inspiration for Naani must remain conjecture. | ||

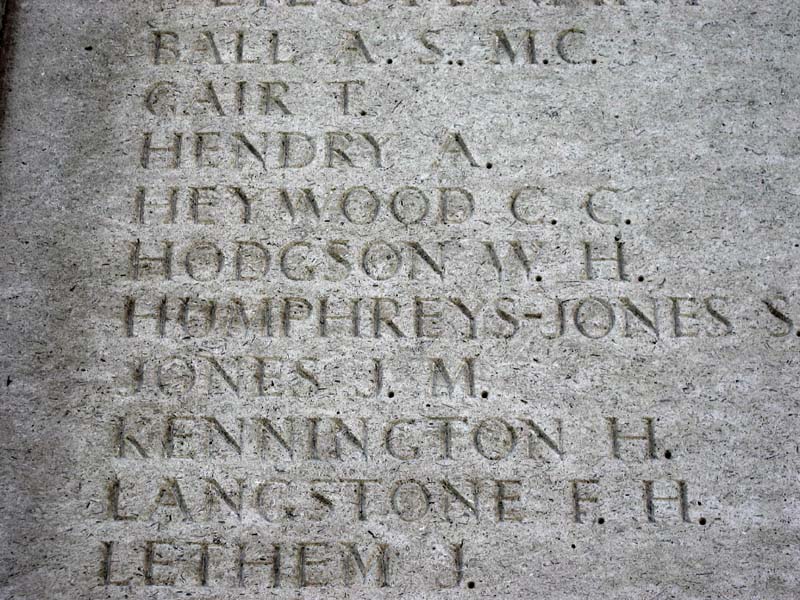

In MemoriamHodgson's entry in the Commonwealth War Graves registry may be found Here

From Peter Kendell I thought you might find this interesting. It's WHH's memorial inscription at Tyne Cot cemetery, near Passendale. My wife and I just returned from a trip to France and Belgium, touring the graves and memorials of various of the War Poets and the Vera Brittain circle, but I didn't want to leave WHH out, especially as we'd visited Tyne Cot in 1998 without knowing he was commemorated there.

| ||

CuriositiesTwo interesting documents provided by Mr Malcolm Farmer:

|

||

Other Pictures

|

| back | |||||||

| The Night Land | Night Scapes | Night Thoughts | Night Lands | Night Times | Night Voices | Night Maps | Night Songs |

| guestbook | Night Speech forums |

little akin to the

book's description, though correctly positioned on a tongue of

rock above a chasm. The caption made no mention of Hodgson's

Blackburn connection, however - an odd omission.

little akin to the

book's description, though correctly positioned on a tongue of

rock above a chasm. The caption made no mention of Hodgson's

Blackburn connection, however - an odd omission.